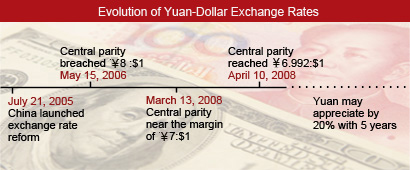

On April 10, the yuan broke the 7-to-1 US dollar point, a major psychological benchmark for the market. It has gained more than 15% against the dollar since July 2005, when it moved from a fixed exchange rate system to a looser one that linked the yuan to a basket of currencies.

The yuan has moved from 8.11 to one dollar into the 7 range about 10 months after the exchange rate reform was launched; thereafter, the pace of appreciation accelerated, and it began flirting with the 7 line since early this year. Finally on Thursday, the yuan-dollar central parity reached 6.9920.

Despite the 2005 reform, China has continued to face challenges to its policy, balancing between external pressure for it to quicken the pace of yuan appreciation and domestic pressure by companies facing rising costs and exporters with less competitive products. With the backdrop of rising inflation and the risk of an economic slide, what policy can benefit both China and the world?

The Steam Behind a Rising Yuan

Though the reform unpegged the yuan from the dollar in favor of a basket of currencies, Chinese regulators still limit the yuan's appreciation on any given day to within a certain band. As a result of this partial shackling, many feel that it is undervalued, and seize the opportunity of its gradual appreciation by investing in Chinese assets, as expectations for future returns are bolstered by the knowledge that the yuan will only become more valuable with time.

Compounded by the relatively rapid depreciation of the dollar, continuous cuts in US interest rates, and the sub-prime mortgage crisis, the yuan and Chinese assets have become a pull for hot money inflows. This demand for the yuan further feeds pressure for its appreciation.

By the end of February, China's foreign exchange reserves amounted to 1.6 trillion dollars, up 57 billion from the month before—an indication of such a continuing influx of hot money. The trade surplus stood at $8.56 billion.

Meanwhile,the consumer price index (CPI) hit its eleven-year high in February, contributed by price surges in global commodities like crude oil and iron ore.

One recent report from the Bank of China underscored the two main incentives for letting the yuan appreciate: to ease export growth and reduce the trade surplus by raising the prices of export products; and to ease domestic inflationary pressure by having a stronger yuan make imports more affordable in China.

What is a Reasonable Rate?

Both at home and abroad, there remained disagreement over the pace of yuan appreciation. Dismay over China's current policy has been especially notable in the US, where the trade gap with China has fueled persistent claims of the yuan being an undervalued currency that unfairly kept Chinese goods cheap, putting US manufacturers at a disadvantage.

In response, China has maintained that the US retail sector was fueled by cheaper Chinese goods, and that only a slow appreciation would be suitable in order to allow Chinese manufacturers to adapt.

Finance professor of Peking University Michael Pettis held that if China wanted to lessen inflationary pressure, it must reduce the inflow of foreign exchanges. He believed the only way to accomplish this was to allow a one-off appreciation of the yuan by at least ten percent to blunt speculation.

Fan Gang, a member of China's central bank monetary policy commission, disagreed, saying that China needed a relatively steady exchange rate policy since it didn't know when the dollar's depreciation and interest rate slide would bottom out.

Bank of China's Global Financial Market Department researcher Tan Yaling stressed that the dollars value too had cyclical crests and falls, and that its depreciation trend would possibly end in the third quarter of 2008.

Tan said it would be unsustainable for the yuan to perpetually appreciate, and that after the Olympic Games, there might be pressure for it to depreciate.

As policymakers and governments are still wrestling over what exactly a "reasonable" valuation for yuan would be, its staggered appreciation over the past 690 over days have trickled down and affected the operations of businesses and individual Chinese.

Pressure on the Ground: Manufacturing Industry

Humen and Chang'an are two towns in China's manufacturing powerhouse of Dongguan City, Guangdong province. In the past three decades, manufacturing companies have multiplied and thrived here. Be it funded by foreign or local capital, the companies shared the same basis for survival—exports. Over time, the creeping appreciation of the yuan has become a common annoyance for them.

A local computer accessory processor Fujikon's marketing manager Ning Yaoxiu said his company earned Hong Kong dollars but paid its staff with yuan, which was a losing formula as long as the yuan appreciates.

According to Chang'an foreign trade director Wang Zhiming, about 65% of the processing companies there operated the same way as Fujikon. Thus, when the central parity moved from 0.98893 to 0.89788 Hong Kong dollars per yuan a year ago on April 10, those companies needed to fork out around 9% more just to pay their staff.

In Foshan, another manufacturing base in Guangdong, two leading electrical appliances produces Galanz and Midea complained that a rising yuan had pushed up costs. Galanz vice-president Yu Yaochang lamented that many foreign companies that were once edged out by cheap made-in-China products were reclaiming their overseas market-share.

Yu said a shrinking external market had led industry players to flood the domestic market with their products, fighting a cut-throat competition through price wars and harming each others' interest further.

Textile and clothing exporters too suffered from declining orders as clients sourced from cheaper destinations like Vietnam and other South East Asian countries. Though facing increased labor and raw material costs, industry players dared not raise prices, fearing further reduction in orders.

Smaller companies were placing their hopes on preferential policies from the government, while those with better capacities tried to upgrade their products and create their own brand names for added value.

The Financial Sector: Risks and Opportunities

As the yuan inched up against dollar, China's financial sector has been stirred as well.

It was generally believed that commercial banks in China, which mainly dealt in yuan, were growing more valuable along with the yuan. Foreign capital attracted by the stronger yuan bolstered bank reserves, and created favorable conditions for banking services.

Meanwhile, US dollar-denominated financial products were becoming less favored by banks like Standard Chartered, Heng Sheng, and Bank of East Asia. Australian dollar-denominated ones, however, were gaining popularity according to sources from the three.

And much of the huge capital inflows into China poured into the futures market. According to Jing Chuan of Great Wall Futures, once speculative capital finished absorbing interest brought by the yuan's appreciation, large-scale underselling might occur and thus cause great volatility in domestic futures prices.

Individuals: Then and Now

Jiang Yong (alias), working for the Bank of China International Securities

"All the foreign exchange assets I have now are 100 US dollars and 200 Hong Kong dollars my friend gave me in 1992. I keep them as mementos," said Jiang.

Having just made up his mind to exchange 2,000 dollars into yuan, Jiang seemed immensely relieved. Things were much different sixteen years ago, when his friend gave him the 100 US dollars and 200 HK dollars as a gift, he said. He hid the money in the bottom of his suitcase in case of severe yuan depreciation. At that time, he recalled, it cost 12 yuan to get one dollar in the black market.

Lai Jinchang, working for the World Bank

Back in the 1980s, Lai was among the "privileged" few who enjoyed business trips abroad and qualified to buy duty-free goods, which the Chinese government set a purchasing quota on. His first trip back from overseas allowed him to buy four items with dollars he acquired from the black market.

Nowadays, his salary is paid in dollars but it is no longer an advantage. As he spends yuan on daily basis, Lai said he has suffered close to 20% in reduced pay in terms of real money.

Liu Jing, entrepreneur

"Dollars reigned over the whole tourism industry at that time. Everything was priced in dollar, even tours from China to Vietnam," said Liu, once a tour guide and now the owner of a tourism agency.

When she first entered the industry in the late 1990s, private consumption using foreign currency was capped at 2,000 dollars. At that time, many Chinese had to use personal connections to obtain dollars. Scores of travel guides, including Liu, thus made a swift side income by trading dollars from foreigners to Chinese travelers.

Today, she's still taking advantage of the currency, but in a rather different way—since 2006, her agency has been reserving hotel rooms for the Beijing Olympics with dollars. The continuous depreciation of the currency later has saved her a fortune, she said.

Reports by Cheng Zhiyun, Zhao Hongmei, An Shilian, Zhang Donghong, Cai Zhijie, Wei Liming, Hu Yiling, Sun Jianfang, Du Yan, Hu Rongping, Hu Zhongbin, Duan Jianming, Zhou Si, Yang Wenyue

Abridged translation by Zuo Maohong and Liu Peng

- Wenzhou Clansmen Take the Yellow Brick Road Abroad | 2008-04-03

- From China Made to China Consumption | 2008-04-01

- Fed Rate Cut Hurts China | 2008-03-21

- Abide by the WTO | 2008-02-25

- Closing a Legal Gap Between China and WTO | 2008-01-09